The monitoring office at BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg documents incidents of (extreme) right-wing interference and influence as well as cases of discrimination in the university context.

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

By using the term 'extreme right', we are using a definition that offers an alternative to topological concepts (horseshoe approach, extremism theory), which are used to construct threatening political 'fringes' and a 'good center' of society at the same time. In contrast to this abbreviated explanation1, right-wing extremism is defined here as the totality of undemocratic, anti-pluralist, historically revisionist and authoritarian attitudes, behaviour, political activities and actions of (non-)organized individuals and groups that proclaim an inequality of people and establish or reinforce corresponding power and domination relations2. We write the word "extreme" in brackets when we make it clear that we are talking about people (groups) whose attitudes can be classified as both right-wing populist (and therefore less ideologically hardened) and far-right. Extreme right-wing ideology legitimizes violence; the very idea of human inequality implies this. For example, the Amadeu Antonio Foundation counts 219 victims of right-wing violence and 16 other suspected cases3 for the period 1990 - today (as of 15.08.2023).Some of the central components of the ideology of modern right-wing extremism will be explained below. These attitudes and associated forms of discrimination are held by many people of different affiliations throughout society; they are not limited to a 'right-wing fringe'.

1 For a critique, see Butterwegge, Christoph (2011): Left-wing extremism = right-wing extremism? On the consequences of a false equation. In: Birsl, Ursula (ed.): Right-wing extremism and gender. Opladen & Farmington Hills, pp. 29-42; Bobbio, N. (1996). Left and right. The University of Chicago Press.

2 Jaschke, Hans-Gerd 2001 [1994]: Right-wing extremism and xenophobia. Concepts. Positions. Praxisfelder, 2nd ed., Opladen. p. 30; Virchow, Fabian (2016): "Right-wing extremism": concepts, fields of research, controversies. In: Häusler, Alexander/Virchow, Fabian/Langebach, Martin (eds.): Handbuch Rechtsextremismus, Wiesbaden, pp. 5-41, here: pp. 13-17.

3 Amadeu Antonio Foundation: Victims of right-wing violence https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/todesopfer-rechter-gewalt/

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

With the monitoring center, we survey various forms of discrimination as well as incidents that we define as right-wing extremist manifestations. We have opted for this broad form of survey for several reasons:

Discrimination is based - first of all semantically - on a differentiation between a "we" group and a group that is constructed as "the others". The ascribed difference is associated with a differentiated value: While the group of "others" is mostly devalued, the "we-group" can valorize itself with various attributes. Linked to these semantic devaluations are disadvantages on a structural and institutional level as well as in the everyday life of society (power asymmetries, socio-economic inequalities, unequal opportunities for recognition), in many cases historically grown1.

The results of attitude research2 show that many people hold discriminatory views or agree with the corresponding items. However, this is not necessarily associated with a closed right-wing world view. We only speak of extreme right-wing attitudes or an extreme right-wing world view when people agree with a majority of discriminatory items, undemocratic, historically revisionist and authoritarian statements3. In this respect, right-wing extremism cannot do without discriminatory attitudes. Conversely, however, there is no causal relationship between agreement with individual discriminatory attitudes and right-wing extremism.

1 Scherr, Albert/El-Mafaalani, Aladin/Yüksel, Gökçen (eds.) (2017): Handbuch Diskriminierung, Wiesbaden: Springer VS.; Scherr, Albert (2017): Sociological discrimination research, in: Scherr, Albert/El-Mafaalani, Aladin/Yüksel, Gökçen (eds.) (2017): Handbuch Diskriminierung, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 39 - 48; Gomolla, Mechtild (2017): Direct and indirect, institutional and structural discrimination, in: Scherr, Albert/El-Mafaalani, Aladin/Yüksel, Gökçen (eds.) (2017): Handbuch Diskriminierung, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 133 - 156.

2 Cf. most recently Decker, Oliver/Kiess, Johannes/ Heller, Ayline/Brähler, Elmar (eds.) (2022): Authoritarian dynamics in uncertain times, New challenges - old reactions? Leipzig Authoritarianism Study 2022, publication in cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation and the Otto Brenner Foundation, Giessen: Psychosozial.

3 Decker, Oliver/Kiess, Johannes/Schuler, Julia/Handke, Barbara/Pickel, Gerd & Elmar Brähler (2020): The Leipzig Authoritarianism Study 2020: Method, results and long-term course, in: Decker, Oliver/Brähler, Elmar (eds.): Autoritäre Dynamiken. Neue Radikalität - alte Ressentiments, published in cooperation with the Heinrich Böll Foundation and the Otto Brenner Foundation, Giessen: Psychosozial, pp. 27 - 88, here p. 50.

Components of (extreme) right-wing ideology and forms of discrimination

There are different terms for racism that is specifically directed against Roma and Sinti*zze, or against people who are considered to belong to these groups. However, the most well-known term, antiziganism, is criticized by many because it reproduces racist insults. The term anti-Romaism responds to this criticism, but lacks the naming of the Sinti*zze. The term gadjé racism changes the perspective and identifies the source of racism against Roma and Sinti: gadjé is a Romani word and refers to non-Roma, among others. Both the term gadjé racism and the term antiziganism emphasize that the phenomenon described is about stereotypes and meanings that "only have something very indirectly to do with Roma and Sinti, but rather with the imagination of the majority population "1 that articulates these resentments.2

Gadjé racism has a long history, which culminated in open persecution and extermination under National Socialism. The Romani word porajmos refers to the Nazi genocide of the European Sinti*zze and Rom*nja.

But even today, Roma and Sinti*nja still experience massive discrimination throughout Europe. Verbal and physical attacks as well as structural and institutional discrimination are also part of their everyday lives in Germany. Due to the long history of discrimination, many of those affected by Gadjé racism are in difficult economic situations and have problems accessing education, work or housing, for example. There is a clear connection here with discrimination based on social origin and other forms of racism.3

Regardless of their actual heterogeneity, Roma and Sinti are imagined as a homogeneous group. They are defamed as having no identity or homeland, being undisciplined and work-shy. It is assumed that "they do not recognize and do not adhere to civilizational principles such as property, laws and wage labour, which are intended for the distribution of goods. Consequently, a pre-civilizational - archaic - form of the "parasitic" is assumed. This is the core of the prejudices and stereotypes described above. "4

Educational institutions in general, and universities in particular, have a special responsibility with regard to the effects of Gadjé racism on those affected by it. Several studies point to a clear educational disadvantage for young Roma and Sinti*zze. We would like to refer to the corresponding recommendations made three years ago, for example by the authors of the ten-year plan to combat antigypsyism at EU level5. A critical approach to discrimination, funding and support programs at various levels and, first and foremost, critical recognition of the problem could be possible answers.

1 Markus End (2011): Images and meaning structure of antiziganism. https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/33277/bilder-und-sinnstruktur-des-antiziganismus/

2 Amadeu Antonio Foundation (2019): Antiziganism - Racism against Sinti*zze and Rom*nja https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/gruppenbezogene-menschenfeindlichkeit/antiziganismus-rassismus-gegen-sintizze-und-romnja-was-ist-das/

3 Ibid.

4 Markus End (2011): "Zigeuner" vs. "Bauer". The social dimensions of modern antigypsyism https://igkultur.at/theorie/zigeuner-vs-bauer-die-sozialen-dimensionen-des-modernen-antiziganismus

5 European Commission (2020): EU Roma strategic framework for equality, inclusion and participation for 2020 - 2030 https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2021-01/eu_roma_strategic_framework_for_equality_inclusion_and_participation_for_2020_-_2030_0.pdf; See also Central Council of German Sinti and Roma (2020): EU strategic framework for equality, inclusion and participation of Sinti and Roma for 2020-2030. Background and position paper of the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma on implementation in Germany. https://zentralrat.sintiundroma.de/arbeitsbereiche/internationale-arbeit/eu-strategie-2030/

Sexism is an ideology that divides humanity into two dichotomous genders: Men and women are ascribed gender-specific characteristics and abilities, activities and areas of life. The male and female subjects thus constructed (or the characteristics and activities with male or female connotations) are valued unequally. For example, some people think that women should do certain tasks and men should do others. "Typically female" activities are seen as less valuable and boys and men are taught from an early age not to behave in a "feminine" or "gay" way, otherwise they will be devalued. Sexism as a structural gender-specific disadvantage has a particularly negative impact on women, who on average continue to earn less than men, perform the majority of unpaid or underpaid care work within and outside the family and are more often at risk of poverty in old age due to (reproductive) breaks in their employment history.1

What is referred to today as traditional gender relations is not much older than 200 years. It developed in the course of social, political and economic changes at the time of industrialization. The ideas of the Enlightenment promised equality for all people, and the prevailing family economy of the time came to an end, calling into question the traditional form of marriage and family. In reaction to this, the emerging bourgeoisie propagated a modernized image of gender from the end of the 18th century onwards. Men and women were assumed to have a specific nature, each with their own character traits. They were portrayed as fundamentally different, with the male being conceived as active, creative, abstract-thinking and the female as the passive, maintaining, compliant part. The newly emerging, separate social spheres - public and private - were gendered accordingly: the man was to be responsible for working in the world, for gainful employment, politics, justice and state administrative tasks, while the woman's place was in the private sphere, i.e. her area of responsibility was the family and household.2 Feminist movements have made it clear that such a gendered division of labour puts women at a massive disadvantage and restricts their gender and sexual self-determination.3

Homophobia, queerophobia and transphobia refer to particular forms of sexism. Homophobia is directed against people whose desires do not correspond to the norm of heterosexuality, for example against women who love women. Queer hostility is directed against people who do not want to and/or cannot assign themselves to the assigned categories of being a woman or a man and see themselves as non-binary, for example. Trans hostility is directed against all those who do not identify with the gender they were assigned at birth. Homophobia, queerphobia and transphobia describe a violent attitude - in thought, word and deed - towards all those who are perceived as sexually or gender deviant. This attitude is based on a repressive-normative world of ideas in which humanity is divided into two dichotomous genders - man and woman - whose heterosexual union is transfigured into a kind of anthropological constant, an eternally repeating ontogenetic telos. Anything that moves outside of this is defamed as unnatural and perverted. Anyone who does not conform to this, who loves homosexually or deviates from traditional gender stereotypes is often ostracized, insulted or even physically attacked.4

Homosexual and transgender people also experience structural discrimination in healthcare, education and training, housing and the labor market. According to a comprehensive study conducted by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency in 2020, for example, 40% of trans* respondents stated that they had been discriminated against by school or university staff in the previous 12 months. The figures are also alarmingly high in other areas of life.5

1 Amadeu Antonio Foundation (2019): Sexism. https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Flyer_GMF_Sexismus.pdf

2 Karin Hausen (1976): The Polarization of "Gender Characters" - A Reflection of the Dissociation of Working and Family Life. https://archive.org/details/HausenPolarisierungDerGeschlechtscharaktere

3 Andrea Trumann (2002): Feminist Theory. Schmetterling Verlag.

4 Amadeu Antonio Foundation (2019): Homophobia and trans*hostility. https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Flyer_GMF_Homo_Trans.pdf

5 European Union Agency For Fundamental Rights (FAR) (2020): A long way to go for LGBTI equality. https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2020-lgbti-equality-1_en.pdf; Lesbian and Gay Association Germany (2020): Experiences of trans* people in Germany.https://www.lsvd.de/de/ct/2628-erfahrungen-von-trans-menschen-in-deutschland

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

Extreme right-wing actors are attempting to open up spaces for their ideologies in the public sphere and in corresponding debates both regionally and nationwide and to promote their normalization. These attempts to take up space are also evident in Cottbus and therefore also in the context of the university. The "increasing normalization of authoritarian and extreme right-wing statements in public discourse"1 actsas a catalyst for violent and discriminatory actions in a wide range of social areas. Those affected in Cottbus also report a large number of such experiences2.

Right-wing extremism researcher Wilhelm Heitmeyer defines extreme right-wing spatial and influence operations as part of a structured escalation strategy aimed at increasingly dominating social spaces and institutions and permanently normalizing extreme right-wing ideologies. Heitmeyer distinguishes between four phases. The initial phase is provocation: extreme right-wing actors demonstrate their claim to power, e.g. through physical presence in public spaces, graffiti, poster and sticker campaigns. All those who are considered 'undesirable' in the extreme right-wing worldview increasingly experience the right-wing hegemony efforts in the form of violence and repression. If the right-wing actors succeed in permanently displacing other groups from the claimed spaces and establishing fear zones, gains in terms of space have become so-called space gains. Without the intervention of a critical civil society, right-wing hegemony ultimately becomes the new normal.3

The BTU monitoring office documents various areas of extreme right-wing use of space and influence in the context of the BTU campus. In addition to obvious attempts at mobilization through posters, stickers or strategies to seize space and words at events, it also looks at less obvious effects of such approaches.

Situations of everyday discrimination, (extreme) right-wing threats and violence

The proportion of international students at BTU is currently 40%. Cottbus is known internationally as an innovative place to study. However, international students encounter an urban society "in which (extreme) right-wing provocations frequently occur in everyday life and in many cases remain unchallenged. In recent years, there have been several incidents in which students of color were affected by racist and extreme right-wing violence in urban society and on campus "4 or people who were read as politically "left-wing" or queer were attacked5. Students of Color also report experiences of discrimination in contact with authorities and offices. "Police checks at the main train station are cited as a specific problem, which are to be criticized as racial profiling and can have consequences for those affected, such as missing important appointments at the university. "6 The effects of extreme right-wing spatial and influence measures in Cottbus can be seen here on a structural level.

Attempts to mobilize in public spaces and on campus

In the context of the BTU campus, (extreme) right-wing use of space and influence can be seen in various forms. In the past, for example, "mobilization attempts in the form of stickers and flyers, the wearing of clothing brands from extreme right-wing fashion labels and the illegal depiction of a campus site in the advertising material of a corresponding company "7 have been observed. In addition, "neo-Nazi cadres attempted to signal claims to hegemony by appearing at public events on the BTU campus. "8 There were also isolated attempts by regional extreme right-wing actors to "contact members of the BTU online in order to spread their ideology. "9

The area of teaching

The challenges in teaching vary in nature and require specific approaches. By far the largest part concerns unintentional, everyday discriminatory statements by students. They are usually made thoughtlessly, are not an expression of a consolidated world view and, as "mental search movements or attitudes, are more or less easily irritated and questioned [...]. The decisive factor here is that teaching staff are appropriately sensitized in order to be able to counter such everyday discriminatory statements in the context of teaching. "10 On the other hand, intended discriminatory statements can also occur in which political orientations are expressed "that are more firmly established in the sense of convictions "11. Intended discriminatory statements "cannot be questioned without further ado; rather, they need to be addressed in the teaching discussion over a longer period of time in order to enable a learning process. "12 The quantitatively smallest part, but one that poses a particular challenge for teaching, concerns people who have a largely closed extreme right-wing world view and/or are organized on the extreme right. This is associated with "problems and questions that have so far hardly been addressed in public at universities and which require specialist debates, monitoring and research in order to be answered. "13 The differentiations outlined above and the challenges for teaching have been described in detail and combined with didactic recommendations for action as part of the action plan against extreme right-wing influence at BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg.

Overall, the aim is to continually create a learning and teaching atmosphere in which academic controversy is possible:

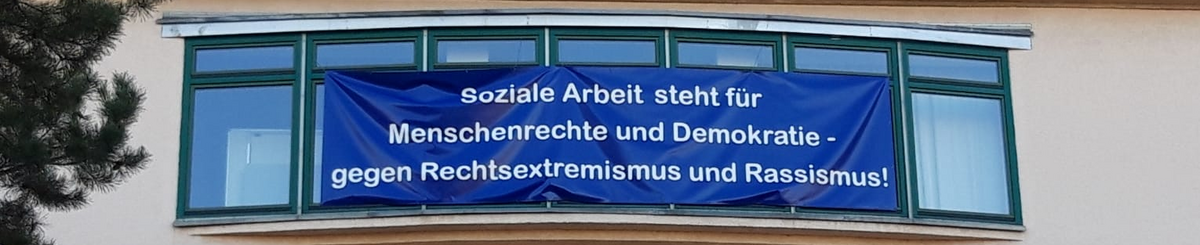

"University is a space in which controversial discussions take place. If this is no longer possible, we as lecturers see it as our task to exhaust all possibilities to (re)create this and to enable a reflective, discussion-friendly and anti-discriminatory learning atmosphere for all students. In doing so, we must ensure that students affected and threatened by exclusion receive the greatest protection by supporting them and clearly demonstrating that we are prepared to do so at all times. "14

1 Radvan, Heike/Dyhr, Susanne (2023): Action plan against (extreme) right-wing influence at the Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg. Sensitized, Positioned, Committed. P. 10. https://www-docs.b-tu.de/presse/public/Handlungskonzept-gegen(extrem)rechte-Einflussnahme-an-der-BTU_RZ.pdf

2 Raab, Michael/Radvan, Heike (2023): "You have to learn to move". Experiences of various affected groups with right-wing dominance in Cottbus; strategies for action and ways of dealing with it. In: Botsch, Gideon/Köbberling, Gesa/Schulze, Christoph (2023): Right-wing violence in Brandenburg. Series Potsdamer Beiträge zur Antisemitismus- und Rechtsextremismusforschung der Emil Julius Gumbel Forschungsstelle der Universität Potsdam. (forthcoming)

3 Heitmeyer, Wilhelm(1999): Sozialräumliche Machtversuche des ostdeutschen Rechtsextremismus, in: Peter Kalb/Karin Sitte/Christian Petry (eds.): Rechtsextremistische Jugendliche - was tun? Weinheim and Basel 1999, pp. 47 - 79, here pp. 67-71.

4 Radvan, Heike/Dyhr, Susanne (2023): Concept for action against (extreme) right-wing influence at the Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg. Sensitized, Positioned, Committed. P. 10. https://www-docs.b-tu.de/presse/public/Handlungskonzept-gegen(extrem)rechte-Einflussnahme-an-der-BTU_RZ.pdf

5 Victims' perspective (2023): Background paper. The focus of right-wing violence in Brandenburg is shifting. https://www.opferperspektive.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/opp_hintergrundpapier_2022.pdf

6 Ibid, p. 11.

7 Ibid. p. 12.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Radvan, Heike/Dyhr, Susanne (2023): Didactic recommendations for action. Appendix: Concept for action against (extreme) right-wing influence at the Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus-Senftenberg. Sensitized, Positioned, Committed. S. 39.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Statement from the Institute SozA BTU Cottbus (26.02.2020): Dealing with right-wing extremist organized students: Statement from lecturers at the Institute of Social Work on current eventshttps://www-docs.b-tu.de/soziale-arbeit-ba-fh/public/aktuelles/2020/Stellungnahme/Stellungnahme-Institut-SozA%20BTU-Cottbus-26.2.20-mit-Unterschriften.pdf

Social background, i.e. the circumstances in which people grow up, determines to a large extent how they will be able to live later on. Social background has a significant influence on what educational opportunities people have and what professions they will later pursue. This is not just about monetary capital, which enables people to attend good schools, take advantage of extra tuition and study - at all or with sufficient time resources. It is also a question of whether people can fall back on the career-enhancing relationships of their parents, whether they have learned in the course of their childhood and youth how to behave in certain social contexts - in accordance with existing norms - or how their own self-confidence is based on biographical experiences.

"Social background is still a decisive factor in educational success "1, according to the Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft e. V., which quantifies the chances of higher education for children from non-academic families as follows: For every 100 non-academic children, 27 begin a degree course, 11 of whom go on to earn a Master's degree, and 2 of whom go on to earn a doctorate. This contrasts with 79 out of 100 academic children who start university, 43 of whom earn a master's degree and 6 of whom go on to earn a doctorate.2

The social marginalization of poor and income-disadvantaged classes also provokes resentment. They are defamed as uncivilized and less intelligent, insulted, laughed at and excluded. This not only serves to devalue those affected, but also to legitimize social inequalities by using classist clichés, especially in times of capitalist crisis. Classism is often intertwined with racial discrimination. Wilhelm Heitmeyer speaks of the development of a crude bourgeoisie, "which, when judging social groups, is oriented towards the standards of capitalist usefulness, usability and efficiency and thus makes the equality of people as well as their psychological and physical integrity vulnerable "3. Raw bourgeoisie goes hand in hand with a tendency to withdraw from the solidarity community of society as a whole and a de-cultivation of the bourgeoisie, which in some cases attempts to "secure or expand its own social privileges by devaluing and disintegrating people labeled as "useless""4.

Universities have a special role to play in combating the effects of structural classism in society. A critical approach to discrimination, funding and support programs at various levels and, first and foremost, critical recognition of the problem can be possible answers.

1 Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft (ed.) (2022): Higher education in transformation. A conclusion after 10 years of the education initiative. P. 13. https://www.hochschulbildungsreport.de/sites/hsbr/files/hochschul-bildungs-report_abschlussbericht_2022.pdf

2 Ibid.

3 Wilhelm Heitmeyer (ed.) (2012): Deutsche Zustände 10. Suhrkamp. S. 35.

4 Ibid.

Racism is an ideology that divides people into groups based on their ascribed origin, culture or religious affiliation, their appearance or their name, hierarchizes them and attributes specific characteristics to them. A fundamental distinction is usually made between the (national) own group and the foreign group(s), between a "we" and "the others". The latter are seen as fundamentally different and not belonging and are usually devalued.1

Racism, i.e. the division of people into (hierarchical) "races", is a man-made ideology that has long been scientifically refuted. It originated during colonization in the 16th century, when European proponents of the slave trade justified their criminal practice by claiming that the enslaved and disenfranchised people were underdeveloped and in thrall to nature and that progress and civilization had to be taught to them by force.2

To this day, racism acts as a social structural principle that controls access to social resources (e.g. via residence permits or citizenship) and legitimizes inequalities. In particular, people with their own experience of migration have poorer educational opportunities3, are more likely than average to be in precarious employment4 and have poorer access to healthcare5. The perspectives and realities of life of people with a migration heritage, Black people and People of Color are often underrepresented in politics, culture and the media. They experience everyday racism in the form of direct verbal and physical attacks as well as structural discrimination, for example in dealings with state institutions or on the housing market6.

Universities have a responsibility to push back and prevent the effects of structural racism in our society. A critical approach to racism, funding and support programmes for the marginalized, but also, first and foremost, critical recognition of the problem can be possible answers.

1 Amadeu Antonio Foundation (2019): Racism - What is it? https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/rassismus/was-ist-rassismus/

2 Ibid.

3 Sebastian Otten, Julia Bredtmann, Christina Vonnahme, Christian Rulff (2020/2021) Kurzstudie: Rassismus in der Schule https://www.rassismusmonitor.de/kurzstudien/rassismus-in-der-schule/; Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung (2020): Education in Germany 2020 https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Bildungsstand/Publikationen/Downloads-Bildungsstand/bildung-deutschland-5210001209004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

4 Samir Khalil, Almuth Lietz and Sabrina J. Mayer (2020): Systemically relevant and precariously employed: How migrants maintain our community https://www.dezim-institut.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Demo_FIS/publikation_pdf/FA-5008.pdf

5 Andrea Rumpel, Rebekka Schalley, Till Behnke (2020/2021): Brief study on refugees in the healthcare system: https://www.rassismusmonitor.de/kurzstudien/gefluechtete-im-gesundheitssystem/

6 Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency (2020): Racist discrimination on the housing market https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/publikationen/Umfragen/umfrage_rass_diskr_auf_dem_wohnungsmarkt.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

Anti-Semitism is hostility against Jews or Jewish institutions, against Judaism as a whole or against everything that is identified as Jewish. Anti-Semitism has a centuries-long history and various manifestations. One of the earliest forms was Christian-influenced anti-Judaism, traces of which can still be found in contemporary anti-Semitism. In the 18th/19th century, modern anti-Semitism emerged as a secularized eschatology in which Jews were constructed as the essence of all modern evil. The conspiracy fantasy of the "Protocols of the Elders of Zion", which originated in Tsarist Russia, popularized a basic form of anti-Semitic ideology that is still effective today: a conspiratorial Manichaean worldview in which (Jewish-apostrophized) evil has conspired against humanity to destroy all good and subjugate the world to its own rule. To this day, many conspiracy narratives vary in this form.

Anti-Semitism is expressed in the marginalization, persecution and expulsion, and even murder of Jewish people, culminating in the eliminatory anti-Semitism of National Socialism, which led to the Shoah, the systematic murder of six million Jews.

Since 1945, secondary or so-called guilt-avoidance anti-Semitism has reflected the rejection of responsibility for the break with civilization. In 2022, 61.3% of those surveyed as part of the authoritarianism study conducted by the University of Leipzig agreed with the statement: "We should devote ourselves to current problems rather than events that happened more than 70 years ago. "1 Today, antisemitism is often articulated semantically and structurally in other forms, such as anti-Americanism, conspiracy narratives - or as Israel-related antisemitism. In practice, the different forms of anti-Semitism are often not clearly distinguishable, but are interwoven with one another.2

In 2016, the plenary of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) adopted the following working definition of antisemitism:

"Antisemitism is a particular perception of Jews that can be expressed as hatred towards Jews. Antisemitism is directed in word or deed against Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property as well as against Jewish communal institutions or religious institutions."3

The following explanation has been added for clarification:

"Manifestations of antisemitism can also be directed against the state of Israel, which is thereby understood as a Jewish collective. However, criticism of Israel that is comparable to that of other countries cannot be considered antisemitic. Anti-Semitism often includes the accusation that the Jews are running a conspiracy against humanity and are responsible for "things not going right". Antisemitism manifests itself in words, writing and images as well as in other forms of action, it uses sinister stereotypes and insinuates negative character traits. "4

In 2017, the then federal government passed a cabinet resolution according to which it adopted the IHRA working definition quoted above (in bold), including the addition:

"In addition, the State of Israel, understood as a Jewish collective, can also be the target of such attacks. "5, as guiding action.6

As anti-Semitism is a historically long-standing problem that is constantly changing and evolving, education and training about anti-Semitism are of great importance7. Even if the restrictive effect of educational programs on the spread and manifestation of anti-Semitism must always be considered limited, there is hardly any alternative to an expectation of effectiveness in this regard8, which applies not least to the university.

1 Oliver Decker, Johannes Kiess, Ayline Heller, Julia Schuler & Elmar Brähler (2022): The Leipzig Authoritarianism Study 2022: Method, results and long-term course. In: Oliver Decker, Johannes Kiess, Ayline Heller, Elmar Brähler (eds.) (2022): Authoritarian dynamics in uncertain times. New challenges - old reactions? Leipzig Authoritarianism Study 2022. Psychosozial-Verlag. https://www.boell.de/sites/default/files/2022-11/decker-kiess-heller-braehler-2022-leipziger-autoritarismus-studie-autoritaere-dynamiken-in-unsicheren-zeiten_0.pdf

2 Amadeu Antonio Foundation (2022): Antisemitism - simply explained https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/antisemitismus-einfach-erklaert.pdf; Amadeu Antonio Foundation (2019): Antisemitism - What is it? https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/antisemitismus/was-ist-antisemitismus/

3 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) (2016): Working definition of antisemitism https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/de/resources/working-definitions-charters/arbeitsdefinition-von-antisemitismus

4 Ibid.

5 Federal Government Commissioner for Jewish Life and Antisemitism (2017): IHRA definition https://www.antisemitismusbeauftragter.de/Webs/BAS/DE/bekaempfung-antisemitismus/ihra-definition/ihra-definition-node.html

6 Ibid.

7 Cf. e.g. Arolsen Archives (2022): Gen Z and Nazi history: high sensitivity and uncanny fascination. P.8. https://arolsen-archives.org/content/uploads/abstract_arolsen-archives_studie-genz-1.pdf

8 Cf. inter alia: Radvan, Heike (2018): The reconstructive view in the field of action of open youth work. Potentials for non-formal education, in: Bohnsack, Ralf/Kubisch, Sonja/Streblow, Claudia (eds.): Forschung in der Sozialen Arbeit und Dokumentarische Methode, Methodologische Aspekte und gegenstandsbezogene Erkenntnisse, Opladen, Berlin und Toronto: Verlag Barbara Budrich, pp. 81-101.

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

Ableism is derived from the word "ability". The term refers to a way of thinking and acting that judges people, human bodies and human development according to normative standards: "the 'value' of a person is determined by what he or she 'can' or 'cannot' do. "1 People are assessed and evaluated according to relatively arbitrary age-, gender- and culture-specific standards. If they do not meet these standards - i.e. if a person of a certain age has not yet developed certain (supposedly) expected abilities - the stigma of disability looms.2

The person regarded as disabled is reduced to their physical and mental condition: "Body, mind and origin are supposed to make up the essence of a person. This links ableism and ableism with other forms of discrimination. "3 Like other forms of discrimination, ableism permanently produces certain normative ideas that serve both as a point of reference and justification for reducing people to specific (dis)abilities and characteristics. In the process, we lose sight of the fact that disability becomes a problem primarily because the design of the environment is geared towards the norm of the (supposedly) non-disabled body.4 Many spaces and public infrastructures - including universities, for example - are still not consistently designed to be barrier-free. There is still a lack of equal access to education, work and political participation. It is these - in many cases avoidable - hurdles in everyday life that create the far-reaching social exclusions that hinder people affected by ableism.5

1 Rebecca Maskos (n.d.): Ableism. https://www.mut-gegen-rechte-gewalt.de/service/lexikon/a/ableism

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Sigrid Arnade (2018): Recognizing and countering ableism. http://www.isl-ev.de/attachments/article/1687/Able-Ismus-bf_2018-bf.pdf

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

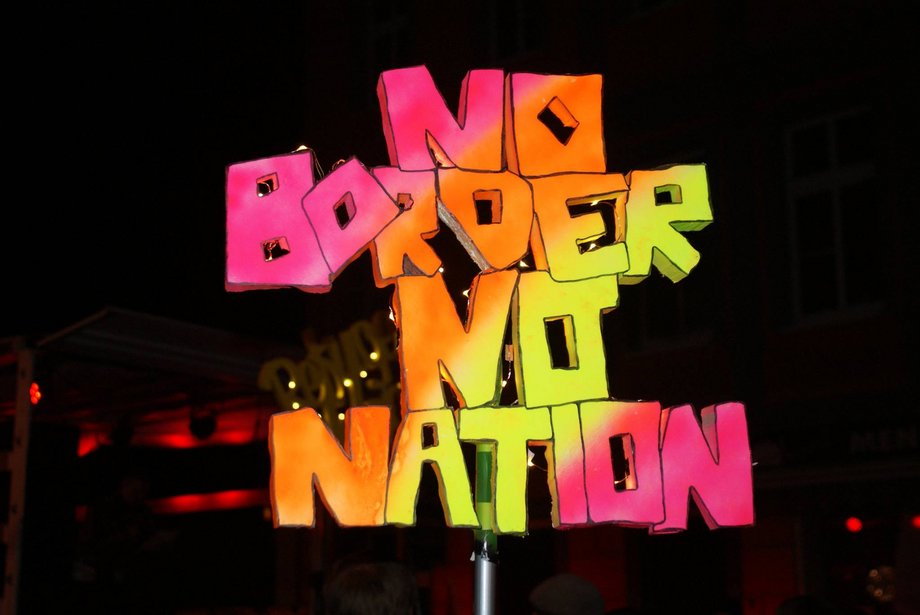

Nation states are an "invention" of the 18th and 19th centuries. The emergence of the first nations went hand in hand with the disempowerment of the nobility, the emergence of a modern state system and the beginning of parliamentarianism. Nation-state structures were also an indispensable prerequisite for the implementation of the capitalist economy. This required legally secured and territorially enclosed economic and public infrastructures in which "domestic" capital found good conditions for its development.1 A competitive relationship was thus inscribed in the relationship between nation states from the very beginning. Nationalism is closely linked to this. It reinterprets the drawing of national borders as a natural one, and sets the difference between (members of different) nations as something absolute and ontological.2 One's own national "we" group is exalted, while all those who are constructed as not belonging are devalued. This applies to other nations and their members, but also, depending on the doctrine, to more or less large parts of the population within the nation, who are regarded as not belonging for racist reasons, for example. Nationalism therefore often goes hand in hand with racism and ethnocentrism.3

Nationalism imagines a togetherness and equality between the members of the "we" group that does not exist, because the national bracket in no way ensures that real existing inequalities in capitalism, such as those mediated by racism, sexism or classism (see above), are abolished. Rather, nationalism conceals real inequalities by hypostatizing an imagined equality. On a global scale, nationality determines how people move, how and where they can live and work. And thus at the same time about the respective opportunities to participate in the extremely unequally distributed global wealth.4

1 Ulrike Herrmann (2015): On the beginning and end of capitalism - Essay. https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/211039/vom-anfang-und-ende-des-kapitalismus-essay/

2 Klaus Schubert & Martina Klein (2020): Das Politiklexikon. Dietz. Licensed edition Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education. https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/lexika/politiklexikon/17889/nationalismus/

3 Wolfgang Kruse (2012): Nation und Nationalismus. https://www.bpb.de/themen/kolonialismus-imperialismus/kaiserreich/138915/nation-und-nationalismus/

4 Theresa Neef (2022): How unequal is the world. Results of the World Inequality Report 2022. https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/ungleichheit-2022/512778/wie-ungleich-ist-die-welt/

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

Ethnocentrism refers to an attitude or worldview in which one's own (social, ethnic, etc.) group becomes the normative standard for evaluating all others. The own group is regarded as normal, good and superior, while all others are devalued in favour of the own group and, depending on their specific characteristics, imagined as wild and uncivilized, immoral and irrational, weak and incapable, etc. Ethnocentrism is thus a kind of meta-ideology that can be found in various forms in many of the facets described here.1

1 Klaus Schubert & Martina Klein (2020): Das Politiklexikon. Dietz. Licensed edition Bonn: Federal Agency for Civic Education. https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/lexika/politiklexikon/17422/ethnozentrismus/; Spektrum (2000): Lexikon der Psychology. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag. www. spektrum.de/lexikon/psychologie/ethnozentrismus/4467

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

Social Darwinism emerged in the 19th century as a kind of application of evolutionism to the developing economic liberalism. The philosopher and sociologist Herbert Spencer had already coined the terms "struggle for existence" and "survival of the fittest" before Charles Darwin. Universal competition within the modern market is like the game of blind forces of nature - just as the best possible adaptation guarantees success in the latter, the latter is also suitable for funding the best possible human characteristics and thus general progress. Even in the historical beginnings of social Darwinism, it was overlooked that it was by no means the case that all people had the same prerequisites to prove themselves in the "struggle for existence". Moreover, the fact that Enlightenment in the emphatic sense should consist precisely in emancipating oneself from the blind compulsion of nature, not in repeating it unconsciously on a cultural level, was disregarded.1

The deeply reactionary and anti-humanist potential of social Darwinism became apparent at the latest in the eugenic and racial hygiene/racist theories that developed at the same time. Eugenicists saw the "races" threatened by degeneration as a result of humanistic progress in the modern age, as natural selection could no longer be effective, and proposed replacing this selection with the selection of the "weak" parts of society (and their forced sterilization, and later, under National Socialism, their murder).2

"Today, the term "Social Darwinism" is used to describe positions that disqualify marginalized groups in society - such as the homeless, welfare recipients or people with disabilities - as "inferior", as those left behind, superfluous, "social parasites" or as people who cause costs to society without benefiting it. In addition to "social Darwinism", terms such as social chauvinism, social racism or classism are also used for such positions. "3 Today, these include the following statements: "As in nature, the strongest should always prevail in society", "There is valuable and unworthy life", "Germans are actually inherently superior to other peoples".

1 Manuela Lenzen (2015): What is Social Darwinism? https://www.bpb.de/themen/rechtsextremismus/dossier-rechtsextremismus/214188/was-ist-sozialdarwinismus/

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

Christian Obermüller, Prof.*in Dr.*in Heike Radvan

Shortly after 1945, there were already calls in Germany for a political end to remembrance and an end to the Allies' denazification policy. Both states, which were founded in 1949, were post-Nazi societies and thus had a responsibility to find a way of dealing with the consequences of the Second World War and the crimes, in particular the industrially organized killing of millions of people in the Holocaust. The GDR saw itself as an anti-fascist state that had given the only correct and necessary response to National Socialism and its causes by building socialism.1 The latter were seen, according to Georgi Dimitroff's definition, in the "most reactionary, most chauvinistic, most imperialist elements of finance capital". Even if the GDR positioned itself very differently to West Germany and, for example, the effect of denazification in both German states should be viewed in a differentiated manner, it must be stated that the GDR's focus from 1949 onwards was on exonerating the majority population with regard to their responsibility for National Socialism. A critical, above all local-historical reappraisal of perpetrators and an accompanying public discourse remained absent until the end of the GDR. Instead, the public culture of remembrance was strongly ideologically shaped and characterized by a heroic depiction of the communist resistance struggle. The various victim groups as well as appeals and mistakes in the work of the KPD were dethematized. In addition, an instrumental approach to Nazi perpetrators was evident, depending on how it could be used in the media for party political and propaganda purposes during the Cold War in the conflict with West Germany.2

In the FRG, demands for a political end to remembrance and an end to denazification policies became hegemonic just a few years after its foundation. In the opinion of the majority of the German population, German guilt for the Second World War and the annihilation of millions of people through the Nazi extermination policy should remain silent.3 The memory of the Nazi era was limited to topics that were suitable for portraying the German "people" as victims of Hitler and the Allies. In many areas of society - including the education sector and politics - people who shared responsibility for the implementation of National Socialist ideology and its crimes remained in relevant positions in West Germany. Even though a broader social debate began in West Germany with the public debate surrounding the Eichmann trial (1961 in Israel) and the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, as well as the attempt by the 1968 student movement to address individual responsibility for the crimes of the Holocaust within families, its impact must be considered limited from today's perspective. In the 1980s, the "Grabe-Wo-Du stehst" movement began local historical research and a partly regional public discussion of the crimes of National Socialism, initially from the perspective of various victim groups, and later also partially on perpetration.

Looking at how both countries dealt with Nazi crimes, it becomes clear that the focus was predominantly on keeping quiet about Nazi crimes in the public sphere. A critical and serious examination of society as a whole with the perspective of taking responsibility - as repeatedly demanded by the public prosecutor Fritz Bauer, for example, and partially fought for in West Germany with the judicial reappraisal in the course of the Auschwitz trials - failed to materialize in both states, or only to a limited extent. Calls for a "line to be drawn" in the public discussion of the Holocaust have received significantly high approval ratings among respondents in attitude research studies for many years.4

Historical revisionism is an essential component of extreme right-wing ideology. With the help of manipulated facts, misinterpreted documents, only selective consideration of historical findings or simply inventions and lies, the historiography of National Socialism, for example, is reinterpreted in such a way that the crimes of National Socialism can be relativized or denied. Right-wing historical revisionists deny or relativize, for example, the Holocaust or Germany's responsibility for the Second World War.5 Among (right-wing) conservatives, a view of history was long popular that denied the anti-republican alliance between extreme right-wing forces and considerable sections of conservatism and the aristocracy during the Weimar Republic, which helped make the rise of National Socialism possible.

However, historical revisionist tendencies do not only exist in the right-wing spectrum. For example, there are efforts by cultural workers from the field of post-colonialism and academics from various disciplines to question the unprecedented nature of the Holocaust and to place it in a universal history of violence in modernity. The respective specifics of historical contexts are lost in the process, resulting in sometimes questionable sequences that assert a historical line of continuity from the violent excesses of the French Revolution to colonial crimes, Stalinism and National Socialism to the settlement policy of the state of Israel6. Many of these universal-historical constructions are characterized by the fact that they largely disregard the findings of historical scholarship at key points - in particular, it is noticeable that there is largely no discussion of the specifics of the eliminatory anti-Semitism of National Socialism. Moreover, at the end of the argumentation, it is often claimed that the policies of the state of Israel represent one of the essential contemporary manifestations of the violence that (constitutively) pervades the history of modernity7 or that the assertion of the unprecedented nature of the Holocaust only serves to ward off criticism of Israel's alleged colonial policies8. Accordingly, the narrative of a universal history of violence can often be described as motivated by Israel-related anti-Semitism. Such universal historical approaches, with their tendency towards relativism and anti-Semitism, have a broad appeal in Germany, as was recently demonstrated in the context of the anti-Semitic incidents at documenta15 in Kassel9 or in the debate surrounding the invitation of Achille Mbembe as the opening speaker of the Ruhr Triennial 202010, and particularly massively in many of the anti-Semitic protests following the Hamas massacre of October 7, 202311.

A representative study from 2022 shows that the generation of 16-25-year-olds in Germany has a growing interest in the National Socialist era. The Nazi era sensitizes "Gen Z to social problems - with a particular focus on racism. "12 However, the study also shows that there is a partial lack of knowledge in this regard. For example, "anti-Semitism as a central ideology of National Socialism [...] is predominantly not recognized/hardly specifically addressed. "13 The results therefore underline both the importance of knowledge about the history of National Socialism and the challenge of adequately conveying this knowledge. Schools and universities have a special responsibility in this regard.

1 Cf. here and in the following Heitzer, Enrico/Jander, Martin/Kahane, Anetta/Poutrus, Patrice (2018): After Auschwitz: The difficult legacy of the GDR. A plea for a paradigm shift in GDR contemporary history research, Frankfurt M.

2 Leide, Henry (2005): NS criminals and state security. Göttingen.

3 Norbert Frei (1996): Vergangenheitspolitik. The beginnings of the Federal Republic and the Nazi past. Beck; Anne Frank Educational Center (ed.) (2020): How the right reinterprets history. Historical revisionism and anti-Semitism https://www.bs-anne-frank.de/fileadmin/content/Publikationen/Themenhefte/Themenheft_Geschichtsrevisionismus_Web.pdf

4 Heitmeyer, Wilhelm (ed.) (2002-2012): Deutsche Zustände, Folge 1-10, Frankfurt/M. as well as the Leipziger Autoritarismus-Studien, which have been published every two years since 2002 by a working group led by Elmar Brähler and Oliver Decker, www.theol.uni-leipzig.de/kompetenzzentrum-fuer-rechtsextremismus-und-demokratieforschung/leipziger-autoritarismus-studie

5 Federal Agency for Civic Education (n.d.): Glossary: Revisionism https://www.bpb.de/themen/rechtsextremismus/dossier-rechtsextremismus/500811/revisionismus/

6 For example, the philosopher Achille Mbembe in his programmatic essay: Achille Mbembe (2003): Necropolitics https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/postgraduate/masters/modules/theoryfromthemargins/mbembe_22necropolitics22.pdf

7 Ibid.

8 For example, A. D. Moses in: Anthony Dirk Moses (2021): The Catechism of the Germans https://geschichtedergegenwart.ch/der-katechismus-der-deutschen/

9 Committee for the scientific support of documenta fifteen (2023): Final report https://www.documenta.de/files/230202_Abschlussbericht.pdf

10 Jüdische Allgemeine (04.05.2020): "Unjustified and unacceptable" - Open letter from Israeli academics: Josef Schuster rejects accusations against Felix Klein. https://www.juedische-allgemeine.de/politik/ungerechtfertigt-und-inakzeptabel/

11 Taz (05.11.203): The anti-Semitism of progressives. https://taz.de/Free-Palestine-from-German-Guilt/!5967918/; FAZ (27.11.2023): The politics of condemnation. www. faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/debatten/udk-berlin-antisemitismus-und-israelhass-treten-offen-hervor-19343147.html

12ArolsenArchives (2022): Gen Z and Nazi history: high sensitivity and uncanny fascination. P.4 https://arolsen-archives.org/content/uploads/abstract_arolsen-archives_studie-genz-1.pdf

13 Ibid. S. 8