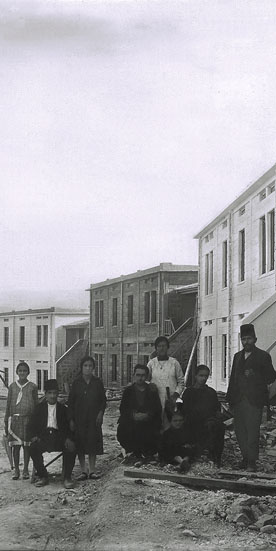

Unsettled modernities: Armenian refugee settlements in French mandate Beirut (1920–1940)

While the question of the Armenian Genocide has been an important research topic in the last decades, rare are the researchers who consecrated their work to the migration routes of the Armenian survivors and their settlement in countries like Lebanon and Syria. Following the Lausanne Treaty of 1923 that allowed Ottoman Armenian refugees to acquire the citizenship of their host countries, large-scale residential quarters dedicated to the Armenian refugees were implemented in cities like Beirut, Aleppo, and Alexandretta, then under French Mandate.

Positioned at the junction of migration history, urban history, and building archaeology, the project aims to construct a history of Armenian refugee settlements in the complex ethno-religious context of the French Mandate in Lebanon (1923–43). It seeks to reveal the ideologies that were at work to reconstruct a lost home and identity for community that had suffered the tragedy of war and displacement.

Focusing on Beirut, it investigates the ideological, political, economical, and cultural stakes at play for the various urban actors. It analyzes the ways in which physical, social, and political intra- and inter-communal boundaries were negotiated and examines how the creation of spaces of identification for the Armenian community interacted with the creation of similar spaces destined to cater to a nascent Lebanese identity. It further focuses on the role of the French in shaping both identities.

Two types of settlements are studied here: planned and self-made settlements. For the first type, the work focuses on the role played by the innovative concepts of modern architecture and urbanism, developed in Europe, in shaping new ways of living for the refugees. It further highlights their pioneering role in matters of urban planning, social housing, and construction technology in Lebanon and, more generally, in the Middle East. For the second type, it shows how rescued skills, traditions, and personal belongings, were purposefully used to reconstruct a distinct cultural identity.

Ultimately the study aims to reconsider the notion of modern European humanitarianism that developed after WW1 and first took shape in the cities of the Eastern Mediterranean. It questions the “secular” and “professional” intergovernmental forms of welfare that accompanied this notion, as opposed to the Late Ottoman legacy that was deep-rooted in the Armenian and the Lebanese communities, in terms of urban planning and architecture of resettlement.

Finally the study also provides insight into the pivotal role these settlements continue to play in the life of the city after their re-use by other groups of refugees - Palestinians, Kurds, Lebanese Shias, and, more recently, Syrians.

Researcher: Joseph Rustom