Vademecum studendi - Why studying?

In this programme, students will acquire the skills to independently study and learn. The task of the teachers is to provide students with a suitable framework and set the proper conditions for learning. Teachers will expect you to deal with the tasks assigned and invest time as needed. Learning ‘how to learn’ is an essential competence that you will need to develop throughout your studies.

How to develop skills around learning and research has been expanded upon by thinkers such the theologian and philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834). The German magazine Forschung & Lehre (Research & Teaching), or F&L, explores this topic in a fictional interview with Schleiermacher:

F&L: ‘Universities have a variety of responsibilities, such as training students for the global labour market and producing research that can be used to improve different industries. But what is the main task of a university in terms of developing its students?’

Friedrich Schleiermacher: ‘Ideally, the university initiates a process for students, namely the initiation of a new intellectual process that students can adopt and apply to their daily lives. The university should awaken the idea of science within students, so that it becomes second nature to look at everything from an objective and scientific point of view–especially anything within the students’ field or within any academic disciplines they study. The university should train students to look at topics independently, but also to see the scientific connections in a larger context. Universities can help students become aware of the basic laws of science in every thought, and precisely by doing so to assist with skills around research, public presentations, and to gradually work out for themselves the business of the university.’

(Grigat, Felix (2018). Friedrich Schleiermacher: Auf die Vorlesung kommt es an. Forschung & Lehre. Alles was die Wissenschaft bewegt. 20.11.2018) To the original text

Attendance of University Lectures and Events Code of Conduct: Courses

At the BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg there is no obligation to attend university lectures, seminars, or events. In studying the humanities and social sciences, learning takes place mainly through discussion and presentation. Therefore, logical thinking, thought development, and the presentation of arguments are developed through repetitive practice. That is why we place great emphasis on your participation in events, even if attendance is not mandatory.

Please arrive punctually, do not let yourself be distracted by food or your phone during lectures, and use the presence of your fellow students and the lecturer for concentrated thinking and active speech participation. You will also notice in good time whether you have understood the topics covered and to what extent they are in line with your own research interests. If you do not understand a theme or concept, ask your lecturer for clarification and discuss it with your fellow students.

You can also involve your lecturer or fellow students in the preparation of your written work. If you use something from these discussions or written comments from the lecturer directly in your paper(s), make sure you clearly cite the source of information. This also applies to other written sources that you use for your work from which you quote or paraphrase literally.

Attempts to deceive in written works, or plagiarism, are quite easy to identify. Style breaks, incoherent use of words as terms, and erratic reasoning are just some ways to identify plagiarism. Before you take the trouble to conceal them, we recommend that you invest time in developing your own text.

Below are some of the most important rules you need to follow to make your paper a work in its own right. Failure to follow these rules will be seen as an attempt at deception and your work will be treated as plagiarism.

The Ethos of Studying

-

It has become fashionable nowadays to regard writing books as the ultimate purpose of study, which is why so many study to write instead studying to know.

You are studying at a time when independent learning and the acquisition of knowledge is not a matter of course. Instead, in many study programmes, studying is seen as a kind of introduction to one’s career and professional life. Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, an intellectual from the Age of Enlightenment, critically notes on the acquisition of knowledge this in his Sudelbücher series. He perhaps would described today’s learning methods as the training of marketable knowledge.

Of course, there is nothing to be said against thinking about securing one’s future at an early stage, where the period of study is more like a kind of prelude to professional life. However, the activity of studying itself can be regarded as its own profession. Studying follows its own rules and takes place in a certain social and institutional context. What you learn during your studies is fundamentally different from what you learn when you have found your profession—or your current profession. Learning refers to an activity that you acquire during your studies and that you will continue to practice throughout your life. In this sense, our ethos of studying is an introduction to professional learning at the university.

The Virtues of Studying at University?

During their studies, students are expected to act in a manner based on virtues such as mutual respect, duty, and responsibility. Think, for example, of the distinction between one’s own and others’ intellectual property or the punctual and prepared participation in seminars.

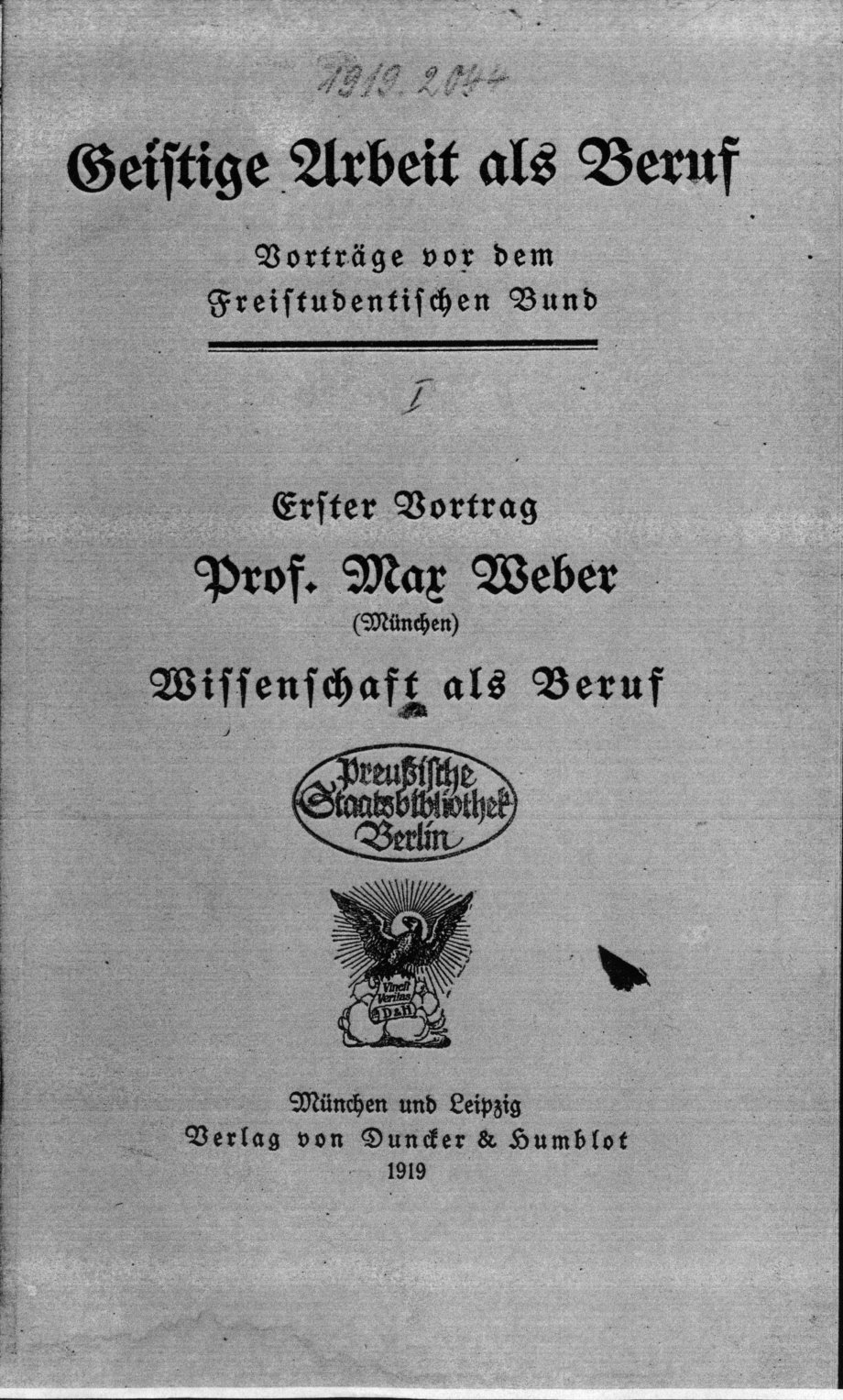

Beyond this practice of living habits, there are other facets of the ethos of a ‘spiritual work as a profession’, as the cultural and social scientist Max Weber explained in his series of lectures in 1917/18 at the invitation of the ‘Deutsche Freien Studentenschaft’, as part of an academic reform movement. Among other things, Weber deals with the question of what distinguishes scientific knowledge from other forms of knowledge and what consequences this has for professional understanding. He suggests that this knowledge is particularly ‘worth knowing’ because it is based on the virtue of intellectual righteousness. It is this virtue, characterized at its core by duty, clarity and a sense of responsibility, which helps the individual ‘to give himself an account of the ultimate meaning of his own actions’ (Weber, Max (1991)). Science as a profession (8th edition). Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, p. 32) For more information, see the original text.

Weber’s reflections on ‘science as a profession’, the social and societal impact of universities, are still being discussed today. Literary scholar Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht takes this up in his essay on the "Task of the Humanities Today" (Ders. (2012). Presence. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, pp. 145-168). He interprets Weber’s writing above as a thesis on the objectivity of scientific research, which consists in the production of innovative thinking. This could also confront ‘unpleasant truths’, but ultimately confirms the social effectiveness of the university in its potential for change.

All these considerations above are an offer and invitation for you to think about what it means for you to conduct your studies in an ethical and professional manner—what consequences could this have for your individual development and for the development of society?

What are the Ethics to follow at University?

Having an environment of ethics and good conduct at the university include having regulations to ensure good scientific practice, avoid plagiarism, prevent conflict, and ensure that there is gender equality in the professional environment. At BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, there are departments for all the mentioned areas areas. Confidential persons are available to assist you if you have problems with lecturers, fellow students or are seeking help for personal problems. On a personal level, this means that you internalise the rules of good scientific practice and develop a keen sense of what your own ideas are and what you owe to other thinkers.

The institution of higher education is an environment onto itself, and possibly each university could be seen as its own microcosm with its own culture. The organisation of the student body and its teachers, the names of the administrative units, study and examination regulations—all these relevant places and documents—can be different in each case. Identify who is the right contact person for what, e.g. student service and programme management for organisational questions, the chairs for content questions, the student council for practical questions. Read the examination and study regulations relevant to your chosen degree programme and find out about the composition of your curriculum, the module and course descriptions, and also the teaching and research areas of the chairs involved in your degree programme. Also take care of the BTU’s event pages, where student and academic activities beyond your own subject or degree programme are advertised.

There are great similarities between universities in terms of quality assurance of academic staff and academic roles. In principle, the ‘Homo academicus’ (Pierre Bourdieu (1984) Homo academicus. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp) passes through a career from bachelor’s and master’s degrees and in most subjects, as an academic assistant, to doctorate or habilitation. In the natural sciences, so-called cumulative doctorates and habilitations are common; in philosophy, for example, ‘a second book’ is written as a habilitation. In artistic subjects and architecture, an academic career does not necessarily require a doctorate or even habilitation. The paper ‘Der falsche Doktor’ (English: The false doctoral) discusses the fact that there are not only differences between disciplinary cultures but also that doctorate processes and their respective titlings changed over time in terms of social and university contexts. Chairs (also at BTU) are filled by means of a call for tenders and a competitive appointment procedure (Univ.Prof., Prof. FH, Jun.Prof.); in addition, there are internal university procedures without a call for tenders (substitute professors; extraordinary professors (apl. Prof.) and honorary professors are either not employed at all or not employed as professors). Guest professors are hired without a selection procedure for a certain period of time; their main purpose is usually to stimulate research. At BTU, there are about 180 professors and 640 academic staff members (as of April 2020, cf. Facts and figures).