Repair Atelier 2019/20 | Projektseminar

Whoever decided to attend “Ethics and Action” with Prof. Astrid Schwarz and Dr. Baruch Gottlieb at the beginning of winter semester 2019 might have expected a lot from the course, but maybe not that their research and learning would move from the seminar room to the museum. They probably didn’t reckon they would have to get so creative either.

The seminar started as most do with the exploration of different theories and concepts. Indeed the students discovered pretty quickly that it’s not enough to read and interpret philosophy of technology and social science texts to get a better understanding of digital objects and their epistemic, political, aesthetic, and ethical aspects. In order to appropriately approach the topic and increase awareness of new perspectives, it was necessary to actually encounter the things being studied. That is best done practically through thought experiments and discussion in the seminar and in group work.

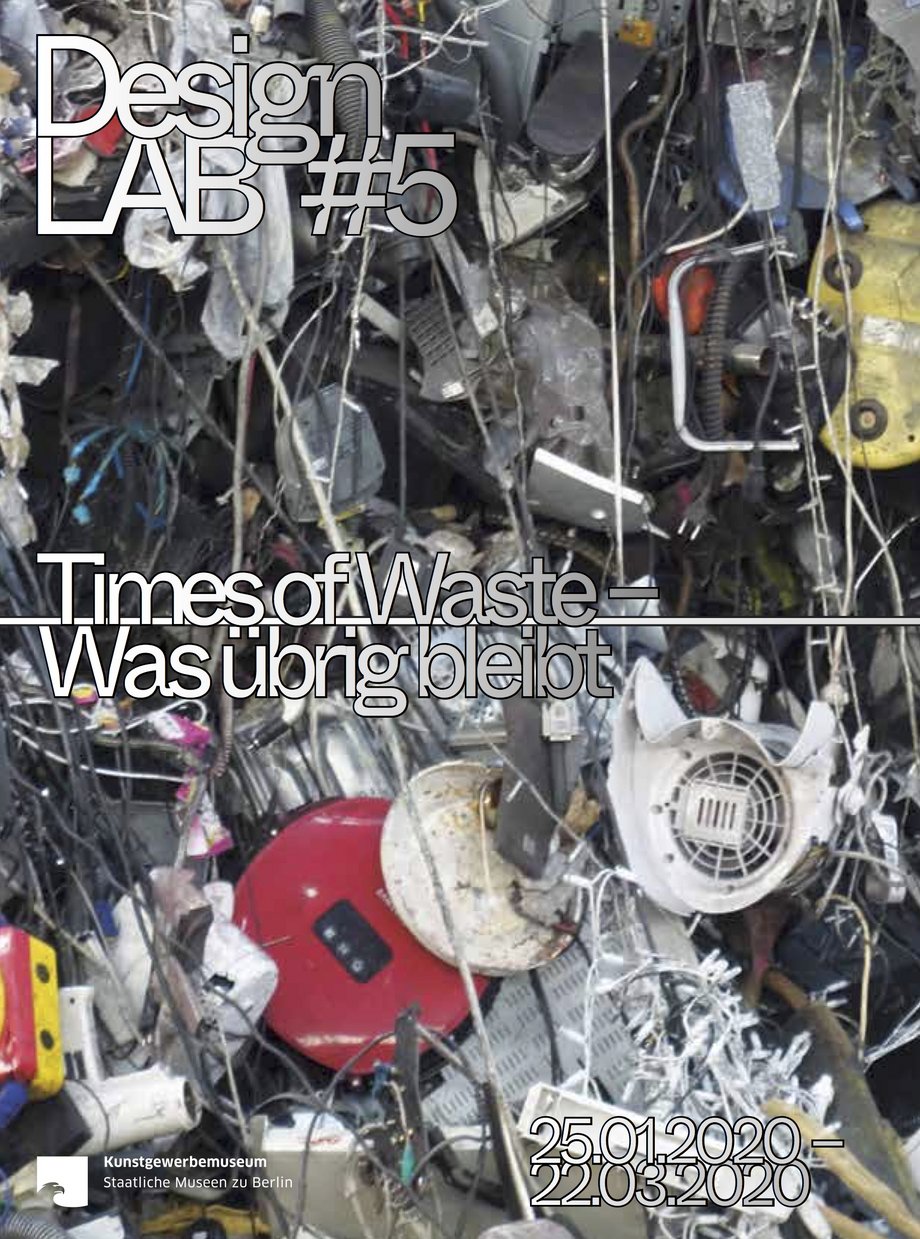

Prof. Astrid Schwarz and Dr. Baruch Gottlieb still took it a step further. The idea: a collaboration with the project “Times of Waste” from the FHNW Basel (University of Applied Science and Arts Northwestern Switzerland) and the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin (Museum of Decorative Arts Berlin). The exhibition “Times of Waste” gives insight into the creation and transformation processes of smartphones. The exhibition opening was set for January 24, 2020, giving the students precious time to work on the project and thinking further.

The students’ impressive amount of motivation made the seminar project possible. In only two months, the students developed their “work in progress” project, Repair Atelier. Students’ project regarded smartphones as repairable, collectible objects. They confronted these objects and scrutinized society’s responsibility for technical objects by asking larger ethical and political questions as to how smartphones and users’ knowledge of them are analysed.

The term “exhibit” has been called into question here. Interestingly enough, the “Repair Atelier” doesn't follow the presentation of objects in the sense of a museum showcase. “Repair Atelier” is understood as a process that lasts the duration of the exhibition. During this time, the objects continually changed. The museum then became a place of encouraged interaction, and the exhibition became a research space.

“Repair Atelier” defines and was themed around the following areas:

- Production: Origin of Materials and Conditions of Manufacture

- Repairing the Smartphone

- Smartphone Users

Exhibition visitors discussed the conditions and possibilities around smartphone manufacture, purchases, waste, and repair. In the regularly occurring events, you could follow and participate in students’ work and research. An exchange in practice and theory, of knowledge, repair techniques, opinions and positions was expressly desired and encouraged.

More Information:

On January 21 and 22 the time had come: in an empty, angled room stood a few tables, stools, and mannequins, where an open place for research was created.

Each team was given a work area, which was designed and prepared according to the respective project, where groups could continue their research in the weeks to come.

A large globe constructed by students was set up, mannequins were dressed, and two work spaces were prepared with a computer and folders full of relevant literature. Projected on the wall behind the work space was a poster titled “Anatomy of an AI System”. A monitor played different repair videos and presented student posters with their work and research questions.

A Kanban board still visualizes the schedule and work status of the individual research projects, along with a poster inviting visitors to participate in the students’ research and work with them.

Full of excitement and fevered anticipation, the seminar participants waited for the opening, which took place on January 24 at 7 pm.

The exhibition opening for “Times of Waste – Was übrig bleibt” (What is left) was followed by a presentation from Clémentine Deliss questioning the “Transformation process(es) in the research of collection artefacts”. Deliss acknowledged BTU’s “Repair Atelier”, and highlighted how the project challenged usual perspectives on an “artefact” and used the exhibition as a research room“—a space in which not only researchers but visitors can participate.

The presentation closed with a tour by Flavia Caviezel and Mirijam Bürgin through “Times of Waste” and then directly after the “Repair Atelier”. The tension was welcomed when it became a clear expression of the visitors’ interest in the overall project and exhibition.

Smartphones: Produkt und Motor der Globalisierung. Eine Projektarbeit (German)M. Vorreyer and A. Skorka

On 6 February 2020, Markus Vorreyer and Ariel Skorka were invited to join the research project. Their topic: “Smartphones—A Product and Engine of Globalization”.

They illustrated the networking paths of a smartphone from its creation to disposal using graphics, texts, and 3D visualization. To complement their theme and to guide visitors through the topic, they installed a repair station. For younger visitors, they organized craft sets to create mini globes.

About 20 to 30 visitors came to the repair studio that day. Unfortunately only a few of them were interested in the project. No globes were made, as a younger audience was missing.

And yet, the day was overall successful. The planned visualizations on the self-built globe (graphics, texts, and 3D visualization) was attractively arranged and implemented in a way that effectively displayed it via a video box instead of a computer. “Automating this was the goal”, said Ariel Skorka.

For one visitor, a mobile phone display was repaired using the existing repair kits and video instructions. There were also one or two interesting conversations for the two students, not only coming from visitors’ questions, but also through an exchange with the museum staff.

Markus and Ariel formed their own personal experiences on this day, but unfortunately, they also encountered some unfortunate events. The exhibition materials experienced some water damage due to a rainstorm the previous night. But this problem was solved and was preventions were taken against future rainy nights.

However, the project is far from being finished, but is a work in progress!

Both Markus and Ariel rate this as a very positive learning experience, and one can be curious about how their project will develop in the following weeks. In order to strengthen and support them and the other groups in this process, more event announcements and advertising for the project days are planned for the following days.

Thoughts on the Presentation

In our globalised world, there are contradictions that must be dealt with.

The most fundamental contradiction negotiates the question of standardization. For example, the first thing man standardized was language. By introducing rules, embodied language—or movement-based expression—lost its value. Oral language soon after evolved into representational and then written language. With the invention of the letterpress and printing, additional rules and forms of expression were introduced, thus standardising language even more profoundly. In this respect, a replacement process of previously-familiar routines and traditions is taking place, which is always accompanied by problems. A piece of culture and history is brought to an end.

But there is also “raw material” from which new patterns of collective action are emerging. This transition is by no means easy, and presents another contradiction: progress.

In a society, innovation and development are always accompanied by unease. While progress often promises improvement, its consequences are intangible in the present. An uncertainty arises, which displaces the initial euphoria with a fear of the unknown.

A dialectic of tension between the contradictions becomes apparent. Globalization is also a standardization. From this knowledge, we must question the origin of our wealth. We cannot praise our progress without recognizing the countries that have made us so rich. Wars happen in the regions from which our products’ raw materials come. These are countries that we have exploited to our advantage and continue to do so. These facts must be considered.

Cultural movements (e.g. the hipster culture), which answer this question with a longing for authenticity and the striving for appreciation, try to counteract progress by applying and returning to historical practices. They are also characterized by "technological disobedience", which manifests itself in the transformation and adaptation of technical equipment to the desired function.

What does this thinking show us? Even if, in comparison to the past, technical equipment is becoming increasingly difficult to repair itself: because for companies, repair leads to a loss of turnover compared to the purchase of new equipment; old things are not the end—but the beginning—which must be recognised. This requires awareness. Because a thing only loses its meaning, or its cultural form. By perceiving and assigning new tasks or functions, it emancipates itself and becomes something new.

Taking up the progress dialectic, repair even provides a social advantage: deceleration. The process of detachment is slowed down and the person can become familiar with a new situation, get to know it, and possibly think about future consequences, ideally to counteract them in present time.

Follow-up Discussion

During the lecture, there were occasional visitors who, at least temporarily, actively followed the lecture, stimulated by the images in connection with the context of the lecture.

The subsequent discussion, on the other hand, was not well received and was exclusively conducted by the students.

Following the lecture, those present asked themselves what the overriding goal of the exhibition, the project “Repair Atelier”, should be.

3 goals became clear:

- The visitors should be sensitized to the topic and encouraged to self-reflect. This goal can be easily achieved by means of pictures and meaningful representations.

- Compile all actionable findings and recommendations in a kind of manifesto, so that they are available to people as a source of information and can prompt thoughts even after the exhibition.

- To be more consciously aware of visitor resistance and to work up arguments.

“Right to Repair” was on the agenda for 21 February 2020, which Christoph Richter, Max Langner and Per-Erik Voegt invited to. The goal of the project was to investigate what museum visitors thought about repairing mobile phones and the practical possibilities surrounding that.

In order to record and eventually track the thoughts and positions of the visitors, the students set up a “Question Catalogue” in front of their exhibit. Visitors received a notecard to write down their questions for drop-off in a special box. The questions were then evaluated at the end of the exhibition. Other participatory activities for visitors included taking apart and reassembling an Amazon Echo Dot.

But it was in fact not so easy, and the visitors needed some guidance. As is often the case when it comes to defective technology, a certain dexterity is required and knowledge of the individual components. But this can be resolved with getting Instructions from the Internet, or so-called repair cafés. These were actively referred to in discussions throughout the project day.

The avalanche-inducing accumulation of electronic waste is a well known problem. All users are confronted with this, regardless of their generation. The problem has been intensified by developers relying on black-box solutions as a common practice, wherein they fail to give more information on how the technology functions. Additionally, there is a lack of information available on individual components, and they are installed in a way that prevents easy replacement. Occasionally, manufacturers offer solutions that whitewash consumer behavior and justify new purchases. For example, with some well-known smartphone manufacturers (Apple, Samsung), customers can receive a discount by trading in their old devices when purchasing a new model. But this discourages the user from reflecting on their consumption-oriented actions.

Visitor reactions were mixed, with the most active group being 50 years and older. Some visitors were reserved and hesitant to enter the studio area. Actively addressing individual visitors helped stimulate conversation.

It became clear through this exercise that openly working and researching in a museum’s exhibition space is still a rare format. Visitors have little experience with this type of exhibit and have a lack of expectation around it. Working in a museum situation was also a new experience for the student-researchers. This form of research-based teaching was, correspondingly, evaluated differently by Max, Erik and Christoph.

In order to better implement the project, it was suggested that the student-researchers get to know the research tools and project aims in advance. The implementation of the overall project was also critically scrutinized. Stronger involvement from all stakeholders was called for in order to achieve greater impact, and also to ultimately increase visitor numbers.

Otherwise, the teaching form was described as a welcome change, even though the its implementation required much more work in comparison to the "normal" seminar course format. In conclusion, however, the three students stated that they consider their project a success. They welcomed the dynamic project environment and particularly emphasized the very good group communication.

The course instructor noted that in the Culture and Technology program, such courses are often not offered as complete modules, but only as partial seminars. This accordingly halves the time investment per project. It may mistakenly picture the effort for a full module seminar as exceptionally high. Also, it has not been common practice in the past to use the teaching format of research-based learning.

Talk: Dr. Claudia Banz (curator, Design LAB #5) and Prof. Dr. Astrid Schwarz (philosopher of technology, BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg)

A recent guided tour at the Museum of Decorative Arts, led by a curator, allowed visitors to view parts of a current exhibition, and invited them to discuss the presented topics with an expert.

For “Times of Waste” and the “Repair Atelier,” there were about ten people in attendance for this guided conversation and tour. The discussion was kicked off with showcasing the entrance area of Design Lab #5 and its strikingly disparate objects. A historical pocket globe, a folding sundial from the 16th century, and a modern smartphone were all on display. Globalization and colonization conceptually connects these objects to the present-day action of making time and space available and storing or categorizing knowledge.

In this sense, these displayed technical artifacts can be understood as “availability machines.” They are tailored to individual use, can be worn on the body, and used at any time and in any place. The stories of the materials contained therein, such as gold or ivory, are also interesting. Their exchange and value of use control the topography of the flow of money and goods. They affect the transfer of knowledge and technology—even today. While gold, for example, was used in the 16th century for the aesthetic and socio-economic valorization of instruments and knowledge objects (like the folding sundial and pocket globe), today it is an indispensable functional component of smartphones.

A long, narrow corridor leads to the exhibition room for “Times of Waste.” Industrial-looking tubes transverse the ceiling while machine noises play from a speaker to set the mood. Here, a central theme of the project is addressed—the material, social, economic and technical manufacture conditions of smartphones. Above all, the exhibit confronts the difficulty of returning such devices to industrial or even natural material cycles after its usage. The transdisciplinary research project at the FHNW Basel has meticulously followed and documented the transformation processes of smartphones and their components over several years, developing an exhibition concept from aesthetic and theoretical perspectives.

Probably the most striking object in the exhibit is a larger-than-life smartphone, enlarged and displayed like an open drawer, or a chamber of curiosities. This gave a better idea of its inner materials, but above all, displayed its eventually-wasted parts. Waste materials that are unable to be broken down and resist "disposal” thus re-enter the world without a trace as new materials. This object represented the inter-relation of socio-economic and material problems of smartphones. Two video installations nearby explained the different typologies of waste materials, how they are generated and processed in waste processing plants and laboratories, only to end up (at best) in landfills.

While recycling is the foreground of the “Times of Waste” exhibit, another important theme from the Culture of Technology is found in the “Repair Atelier”, which presents the idea of repairing. Both recycling and repairing are strategies dedicated to the sustainable management of resources and products. Whereas recycling focuses on efficiency in the reusability of materials, requiring the destruction of an item, repairing is about the preservation of the technical item’s functionality, including social and emotional relations. A certain smartphone, a certain radio or a certain hand mixer should remain in use and guarantee the user continuity and recognizability in the age of the disposable society.

The Cottbus students’ projects were briefly presented, including a status update on their ongoing activities. In an open discussion, more and more questions were asked about the social significance of repairing. This included to what extent this cultural technology is generally available. Specifically in relation to digital devices, people questioned whether repairing is even sensible given planned obsolescence and how technically inaccessible digital devices are made in particular. Another focus of discussion was the question of how the landscape of repair cafés empirically presents itself, i.e. which age groups are represented there, how knowledge is exchanged there, and motivations for repairing. The few studies on this topic so far only show that it is less a question of economics than of acquisition strategies in dealing with everyday things. It is overall a rather complex process. Consequently, this process is not limited to monitoring technical processes, but rather opens up a question-and-answer game in which social development and cognitive competencies are at stake, as well developing a practical understanding of world relations in the best sense.

The Corona crisis is slowing down our lives in many different aspects, including teaching conditionsand unforeseeable challenges to time management. Our project, “Repair Atelier”, will be exhibited at the Museum of Decorative Arts Berlin longer than originally planned, although the museum remains closed to the public. “Repair Atelier” will be available again as soon as the museum re-opens. There will be further opportunity to experience students’ work from last semester’s Culture and Technology seminar, which covered topics about the cultural and technical implications of recycle and repair. The “Repair Atelier” was developed at the invitation of FHNW Academy of Art and Design Basel, and was incorporated within the Times of Waste exhibition at the Museum of Decorative Arts Berlin.

While initially planned as a seminar at BTU about epistemic, political, aesthetic, and ethical aspects of digital objects, it evolved into an exploratory learning-by-research project with a main focus on the smartphone as a repairable and collectible object. Literature touched upon the topic of repairing culture within Philosophy of Technology, Material Studies, and History of Science. Students followed ethical and political lines of inquiry about care and responsibility towards and with technological objects. Black box objects, planned obsolescence, throw-away society, user types, global material flows and local re-use were important keywords and encompassed the cultural reinterpretation of technological things in general.

Additionally, the museum served as a space for translating these questions into design concepts. Museum visitors have been invited and encouraged to engage with the projects of “Repair Atelier”, including visitor surveys, participatory activities that included smartphone repair, active discussion, and expert-led lectures.